Transcript

NARRATOR:

These are the sounds of a tsunami warning. They alert residents that a killer wave is about to strike. These sirens, however, are just a small part of the sophisticated warning systems that played a role in Japan and in the U.S. during the Pacific Ocean tsunami in March 2011.

Most Tsunamis are generated by an undersea earthquake. Fortunately, Japan has one of the most advanced earthquake early-warning systems in the world. It detects tremors, calculates the epicenter, and sends out warnings from over a thousand seismographs scattered throughout the country.

The Japan Meteorological Agency issues the warnings and sends alerts to television and radio channels, the internet, and mobile phone networks. When the earthquake struck 80 miles offshore, warnings were generated in about three seconds.

The tsunami warnings came three minutes later. These take longer because more complex calculations are involved, and must factor in ocean data. Since the first tsunami waves struck the coastline within 20 minutes, the advance warning provided some residents with crucial minutes to reach a safe area.

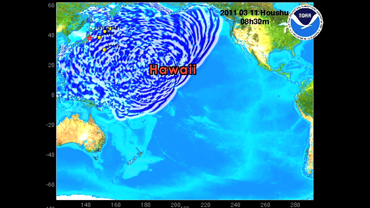

While the earthquake sent powerful tsunami waves westward toward Japan, the tsunami also propagated east into the Pacific Ocean.

Here, warnings are issued by the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, operated by NOAA in Hawaii.

NOAA maintains a large network of buoys with ocean floor sensors that are strategically positioned in the earthquake-prone zones of the Pacific. This system collects vital ocean data for tsunami forecasting.

On March 11th, only 25 minutes after the earthquake struck, the first buoy station registered the tsunami and relayed information to Hawaii.

Scientists used this data to run models and issue forecasts and warnings to nations throughout the Pacific. From there, local emergency managers decided what actions were appropriate to take for public safety.

The earthquake and resulting tsunami devastated the Japanese coastline, causing damage that will take years to repair. While we can’t prevent these forces of nature from happening, our early warning systems can help us prepare for the dangers headed our way.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.