Transcript

NARRATOR:

On March 11th, 2011, a powerful tsunami hit Japan, destroying cities and villages. As the water receded back into the ocean, it pulled what remained of buildings, cars, boats, and homes along with it. Scrap metals, plastics, and objects of all shapes and sizes either sank near the shore or floated away. In the days that followed, large masses of floating debris could easily be seen by satellite imagery and aerial photos.

In the wake of this disaster, NOAA is assessing the potential impact that the debris may have on U.S. shores.

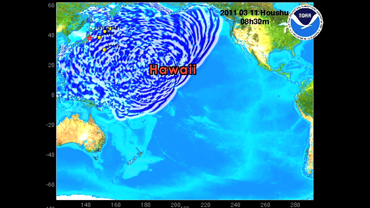

So, where will this debris go, and when will it get there? To help answer those questions, scientists are using computer models to estimate the debris’ path using its starting location in the tsunami zone and historical weather and ocean conditions.

The findings are that some debris could pass near or wash ashore in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands as early as this winter. Debris may also approach the West Coast of the United States in 2013, and potentially circle back to the main Hawaiian Islands in 2014.

But scientists caution that there are limitations to what computer models can tell us. Now that the debris has moved out of satellite view and with currents and winds in the Pacific constantly changing, there is no guarantee that the debris will stay on the predicted paths. Itemswill sink along the way or break up and disperse in many directions.

Despite these unknowns, NOAA and its partners are collecting data, assessing possible impacts, and making preparations in case debris does wash ashore.

The 2011 Tsunami in Japan reminds us that the devastation that happens on land can also become a marine debris issue at sea.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.