Transcript

NARRATOR:

During World War II, American sonar researchers encountered a mystery - an echo from what seemed like the ocean bottom, but at depths where no bottom should be.

Even stranger - the false bottom moved. Deep in daytime, it crept closer to the surface as the sun went down.

Was this “phantom bottom” enemy submarines? Water currents? Or maybe something more mysterious?...

Trawling the depths with nets and dives by early submersibles revealed the answer: fish. Trillions and trillions of them. The sonar mystery revealed life in a part of the ocean where none was thought to be: the mesopelagic zone.

The open ocean - everything except the coast and bottom - is not the same at different depths. It’s made up of habitats defined by currents, pressure, and temperature, but most of all by light. From the surface to around 200 meters is the epipelagic zone. Enough sunlight can penetrate here for photosynthetic organisms to thrive, and abundant life feeds on those organisms.

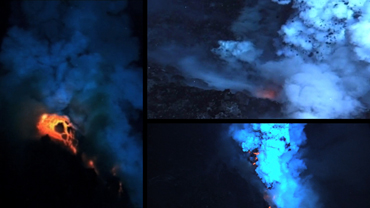

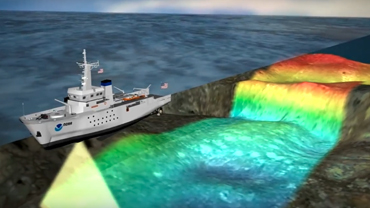

The mesopelagic is below, from around 200 to 1000 meters. Though the ocean is often much deeper, that’s deep enough that almost no light penetrates, making it very hard to explore - until recently.

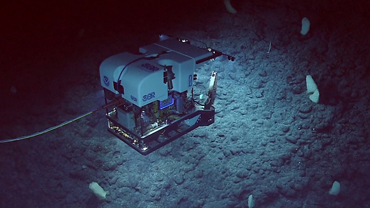

New technology brought to bear by ships of exploration like NOAA’s Okeanos Explorer are starting to help expose the mysterious creatures of the mesopelagic.

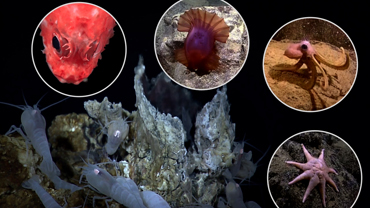

The water can seem empty…but remotely operated vehicles’ with advanced cameras reveal a wild riot of colors, shapes, and bioluminescence.

These jelly-like animals don’t survive net surveys, so their behaviors are often being seen for the first time.

Krill and many types of squid are abundant… in some places, astonishingly so.

There are also fish - like these saw-toothed eels that hover vertically in the water, waiting almost invisibly for prey to pass above.

In fact, there are so many fish here that recent studies estimate that up to 10 billion tons of fish - or 90% of the fish in the world, by mass - are found in the mesopelagic.

Just one family of fish called bristlemouths may number a quadrillion, which is a thousand trillion!!! This makes them the most numerous vertebrates in the world.

Although many of the fish here are tiny, they occur in huge numbers, and they are always on the move.

These animals - fish and invertebrates - make the up and down journey that researchers discovered, twice every day.

What’s truly amazing is that we now know it’s part of the largest migration, by mass, in the world!

This migration helps fill in some of the missing links in scientists’ understanding of the ocean food web.

Mesopelagic animals rise in the evening because they’re feeding on plankton near the surface.

As the sun rises they sink back into the dark to hide from predators.

They don’t all succeed. One reason marine mammals like elephant seals, king and emperor penguins, and some large fish like bigeye tuna and swordfish dive so deep is to feed on animals here.

Understanding the connection between some of the fish we like to eat and mesopelagic creatures shows us that we need to be careful about impacting this habitat too much.

And we wouldn’t be the only ones affected. When small mesopelagic creatures make waste, and when they die, they produce what is called “marine snow.” In the total darkness of the deep ocean, falling marine snow is THE major food source for many bottom animals like corals and sponges that form their own amazing ecosystems.

Creatures in the mesopelagic have, up until recently, been relatively safe from major human impacts, but increased pollution and overfishing could have huge consequences. Some fishing industries are now developing ways to harvest tons of small mesopelagic creatures, which could disrupt the food chain.

But doing this important research now into the mysteries of the mesopelagic gives science a chance to get ahead of commercial exploitation. If we keep searching, good data will fuel smart policies to support sustainable use of this virtually unexplored frontier.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.