Transcript

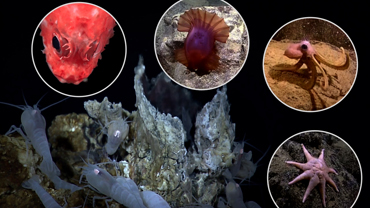

Some of the earth’s most stunning and diverse habitats are found in the darkest depths of the coastal ocean: clusters of cold-water coral and sponges, towers of eggcase spirals, and fluffy mats of methane-eating microbes. These microbes build diverse ecosystems and, despite their size, are responsible for some of the most thriving habitats in the dark realms of our coastal ocean.

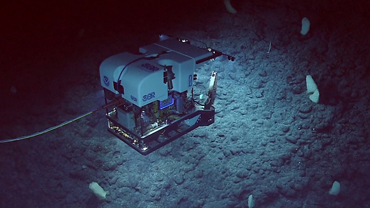

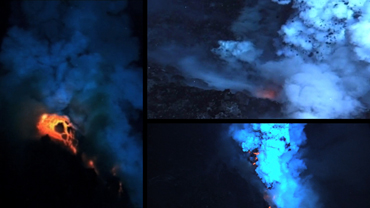

Meet the chemosynthetic microbes: tiny single-celled organisms that convert chemicals into energy to grow. As marine life dies and sinks to the seafloor, it gets buried. And as it decomposes, it slowly builds up methane. Over time, this methane gas escapes through fissures and releases into the water column, forming methane seeps often between 600 and 5000 ft. At these depths, beyond the sunlit zone of the ocean, chemosynthetic microbes become the architects of life, building rocks for larger organisms to live and hide on while also feeding some of them.

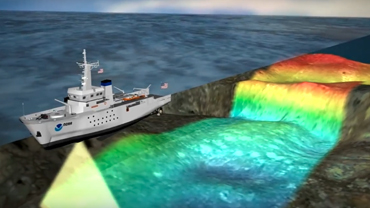

Though similar to Hydrothermal vents, these habitats are not hot, earning them the name cold seeps. Recent explorations of our coastal ocean have surprisingly uncovered thousands of cold seeps off the U.S. coast.

Methane seeps are crucial to both marine and human life: they are considered essential fish habitat for fisheries management on the United States Pacific Coast and scientists continue to discover abundant commercially harvested fish species living there. Another crucial service is that these gas-loving microbes actually consume methane, keeping this greenhouse gas locked in the seafloor and out of our atmosphere. Future research may uncover novel medicines that these biodiversity hot spots provide.

And while these epicenters of diversity occur beyond the sunlit zone of the water column, they are important to all life on the planet and our exploration of them has changed scientific understanding of our coastal oceans.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.