Transcript

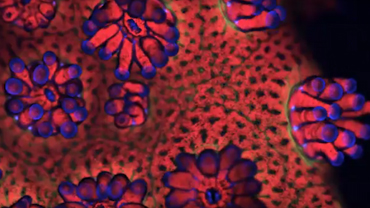

Amy Eggers: So this is a close-up of a coral polyp. And these red dots are the individual algae cells, so the symbionts that live inside the coral tissue."

NARRATOR: Coral reefs are gigantic, but corals themselves are very small. And the things scientists like Ruth Gates at the University of Hawai’i need to know about corals happen at such small scales that it takes a million dollar microscope to see them.

Ruth Gates : This is a laser scanning confocal microscope. This microscope is the only microscope in the world that allows us to image corals, live, in simulated future ocean conditions that are warmer and more acidic, and we can watch the response, on the microscope, of a living animal.

NARRATOR: Why do they need to look close enough to see inside a coral? Because corals are in trouble, and the solution to their rescue might be within.

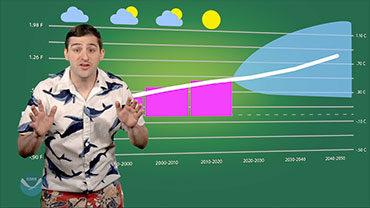

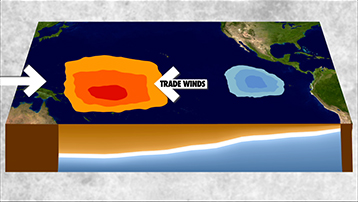

Corals around the world have been declining for some time, but the years from 2014 to 2017 were devastating. Abnormally hot water caused a global bleaching event, only the third ever, and the longest in recorded history.

Mark Eakin: The past few decades we have lost about half of the world’s coral reefs. In the last three years we lost another twenty percent of what was remaining. The problem is as the oceans continue to warm we’re going to lose more and more corals. In fact climate models are predicting that ninety percent of the world coral reefs will be seeing the temperatures that cause bleaching every single year by mid century.

NARRATOR: The reason hot water causes corals to die off is well understood. Corals have algae called zooxanthellae living inside their cells, and giving them energy through photosynthesis. The algae can also get too hot, and when they do, they release chemicals toxic to the coral. The coral ejects the algae and turns white, or “bleaches.”

But Ruth and others have found that some “super corals” bleach less easily, or recover faster. Now they can start to see why.

Mark Eakin: Some corals have a mechanism that allow them to be more tolerant to high temperatures. By using the confocal microscope scientists can go in, find these corals that are more tolerant to high temperatures and potentially use these for breeding to try and develop super corals.

Ruth Gates: These bright green patterns, those molecules protect the algae. We actually don’t know why they’re important in the system. That’s why science is so amazing, we’re always discovering new phenomena, or features.

NARRATOR: They do know that corals can host different types of zooxanthellae. And some of these might be “super algae” that do better in high temperatures and acidity, too. And if that’s the case, can scientists help make that relationship even better?

Ruth Gates: One strategy we’re looking at is to try to give corals the best zooxanthellae they can possibly have. And so, can we take the ones that aren’t very good at facing temperature out of the system, and put back zooxanthellae that are better at facing higher temperatures and surviving.

Mark Eakin: Corals take hundreds to thousands of years to adapt to warming conditions, and we don’t have that long. By breeding super corals through this process known as human assisted evolution, and finding the best algae to go with those corals, we may have an opportunity to try and do in just a decade or two what the corals would do over hundreds or thousands of year.

Over the last ten years or so there has been a great advance in using coral nurseries, fragmenting corals and growing them back and putting them out on reefs. But you can’t restore a habitat when the problem is still there and as temperatures rise, we need the super corals, we need the corals that tolerate high temperatures. So the challenge for the next scientists, the next engineers, is to find those answers for how do we grow them faster, how do we grow more of them, how do we plant them fast enough to be able to spread corals out and restore coral reefs all around the world. That’s what we need to make a coral comeback.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.