Transcript

JIM DELGADO:

So much of history has really been tightly kept in a little box that archaeology is now cracking open. I started in archaeology when I was fourteen. And I figured, “What could I do? What was left to be found?” 95% of the oceans remain unknown. So if you want to go explore, if you want to find something, the oceans are a tremendous place to work.

My name’s Jim Delgado, and I’m a maritime, or underwater, archaeologist.

Maritime archaeology is the study, from what people leave behind, of how we as human beings have interacted with the oceans and with lakes and rivers. It goes back thousands of years, tens of thousands of years, as people harvested goods from the sea, learned how to fish, built the first canoes to cross the oceans, to today’s modern times when big massive ships ply the oceans carrying oil, large numbers of people, and in the 21st century, still transport 90% of the things that people buy and use by water.

In my career, I’ve been able to find a great deal. I’ve seen ancient ships from a time when the Mediterranean was an expanding area of different cultures from ancient Egypt to the Phoenicians, to the rise of the Greeks and the Romans, I’ve worked on ships from medieval periods, I’ve worked on ships in the far East, including a fleet that Kublai Khan, the Mongol emperor of China sent to try to invade and conquer Japan in 1281. I’ve been able to work on more modern wrecks too, from Titanic, to lost ships from World War II, to ships sunk at the end of the second World War that were lost when they were atomic bombed as the United States was testing this new and powerful weapon.

No matter what type of history it represents, no matter how old it is or how new it is, for me the thing that is most powerful is when I see things on these ships that connect me to the people. Human beings built these ships with their hands. They sailed on them and operated on them, working with one another. Whether they’re up climbing and moving sails and hauling ropes, whether they’re down in an engine room shoveling coal or turning a valve, whether they’re firing a gun or taking a navigational sighting. In some cases they’re passengers, they’re sailing on these ships, to start a new life in a new land, or they’re exploring, or they’re going to fight someone. For all of that, when they live in that ship, they are their own community, they’re a village, they’re a town, and when you as an archaeologist dive on those ships, you find the evidence of what they did. And in some cases, you find them. And with that, you learn a great deal, not only about the ship, but about the people. Because ultimately, for me archaeology isn’t about things. It’s about people.

The progression of how people have changed in response to the oceans, but now how the ocean is changing in response to us, that’s where I think it really becomes relevant. More of us need to be out there, bearing witness not just to new discoveries, not just to the past, but to what we see now. We need to share more of the oceans and why they’re important with the rest of the country and with the rest of the planet.

When I first started as a maritime archaeologist, you would go out in a boat, you would take a look at a spot on the land and another spot, and if they lined up right, you’d figure you were more or less over a shipwreck that you plotted, you’d jump into the water, you’d swim down, and there it would be. And you might share that with the other diver that was with you.

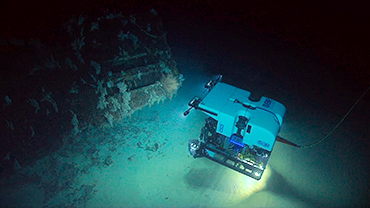

But these days, increasingly we’re using new technology, satellites that tell you exactly where you are on the surface, robots, highly sophisticated cameras, the internet, to broadcast what we do to a global audience so that you, the visitor, the person that’s looking on can participate in discovery, exploration, and most recently, even the excavation of a shipwreck in some cases thousands of feet deep.

The way archaeology works is often times it gives us information that isn’t in the history books. In some cases, there are no history books. Ancient cultures didn’t write books. In other cases, that knowledge has been lost, the books have been burned or they’ve disappeared. In other cases, archaeology talks about things or talks about people who don’t usually get into the books.

In the past, much of the history that was written was about men, about white men, about Europeans, about great explorers. You could hear about Columbus in the history books, but what about the Spanish sailors, and the Portuguese sailors, and the other people that lived and worked? At the time he’s sailing, what about all these different people that are out there fishing on the water? What about children? What about women at sea? And what about aspects of history that we haven’t heard much about because we either can’t read that language or those records are gone?

That’s the power of archaeology, and in particular, that’s the power of maritime archaeology because unlike sites on land, many ships sink to the bottom, and unless they are found by somebody or a fisherman’s net snags something, they’re left alone, and they become almost like a time capsule for us to learn from.

You would think that because the ocean is a harsh environment - it’s cold, it’s strong, it’s got currents, it’s full of salt - that everything is going to be eaten up. And in time, things do go away. But what we’re finding is that just like you have different climates on land, you have them the bottom of the ocean. So in some cases the water may be less salty. In the Baltic and in the Arctic, wooden ships are still very nicely preserved. I swam into a wreck in the Arctic, and in those freezing waters, there was a book still sitting on a shelf that you could open and read. And it had been on the bottom for nearly 70 years.

There is good news for people that want to protect the oceans. And that is marine protected areas, but in particular, in the United States, it’s National Marine Sanctuaries. Sanctuaries were created specially to preserve, to protect, and to share why they’re important with the rest of the country. These areas are all very important because inside them, they protect not only coral reefs, and fish populations, or the migration routes of whales or sharks, they also protect thousands of shipwrecks. These wrecks are protected and they sit in a way as exhibits in an undersea museum.

At Thunder Bay, hundreds of shipwrecks, almost perfectly preserved by the cold fresh waters of Lake Huron, are available for divers to explore and to dive in while the maritime heritage center back at the sanctuary’s headquarters in Alpena, Michigan, gives visitors on land a chance to see what these ships are all about. Why they’re important, what they look like, how they went to the bottom, and the people’s stories associated with them.

On the west coast of California, we’re working now to document more of these shipwrecks and discover wrecks that the history books or old newspapers say to us are out there, but we haven’t yet seen or put our eyes on them. So over the last few years we’ve discovered a few of those wrecks, and most recently we found a wreck that wasn’t supposed to be there at all. It was a ship that had sailed out and disappeared almost a hundred years ago. It still remained undiscovered and one of the top mysteries of the ocean. Until a regular survey of Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, we found a shipwreck, and as we looked at it and examined it, it turned out to be this long-missing ship with fifty-six crew.

So not only were we able to solve a mystery, not only were we able to say this is a very important wreck sitting here and protected in this sanctuary, but we were able to reach out to the families of those fifty-six men and say, after ninety-five years, we know where your grandfather, your great-uncle, your cousins - we know where they are. They’re at peace resting at the bottom of the sea, in a shipwreck that is now full of marine life. It is their grave, but it is also part of a rich and important marine sanctuary that has been set aside to protect such things. Not only do I think that gave these families some closure, an opportunity to say, “at last I know what happened,” but also some satisfaction, that we’re looking out for these guys, as we do so many other things in the marine sanctuaries system.

One of the things that we've learned when we look at shipwrecks in particular but other parts of archaeology is when something is preserved, when it's set aside it's almost like money that you put in the bank, but it's money that you can't make another deposit to once you start taking it out it's gone forever. That's why as archeologists we're very careful to look and not touch more often than not.

In the time I've been an archaeologist I've seen the technology changed so much that if I could go back and say, "hold on don't dig that ship up now let's wait 30 years or 40 years because we'll learn twice as much," I would go back and have that conversation with myself and others.

But by the same token to what we also learn is that these shipwrecks, not only are repositories of the past, they're the people's graves in some cases, also wonderful marine habitats full of life so why should I as an archaeologist go to the bottom and say okay we're gonna take all of this marine life off, we're gonna take away this home for all these fish and we're going to bring it to the surface, when it's there sitting as an untouched museum that meets all of those needs, or that's a beautiful place for divers to go and visit.

That's why we have sanctuaries. That's why we set these areas aside. It's not to just go and take, it's to look, to observe, to appreciate, and in a few cases if it's that important to intervene, take maybe this or that, a doctor when he operates doesn't take everything out of you he might take a little biopsy as a sample to learn what's making you sick, and so that's how we approach it with shipwrecks.

That's how we approach it with most any anything in a Marine Sanctuary. They are sanctuaries, they're conservation areas, they're sentinels that speak to how we are changing the oceans and how we're also working very hard to save the oceans and preserve what's in them. So we for the most part leave only bubbles and take only photographs.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.

An official website of the United States government.

Here's how you know we're official.